Report of 255 Clinical Ethics Consultations and Review of the Literature

- Research

- Open Access

- Published:

Clinical ethics instance consultation in a university department of cardiology and intensive care: a descriptive evaluation of consultation protocols

BMC Medical Ideals book 22, Article number:99 (2021) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

Clinical ethics case consultations (CECCs) provide a structured approach in situations of ethical uncertainty or conflicts. At that place take been increasing calls in recent years to assess the quality of CECCs by means of empirical research. This study provides detailed information of a descriptive quantitative and qualitative evaluation of a CECC service in a section of cardiology and intensive intendance at a German university hospital.

Methods

Semi-structured certificate analysis of CECCs was conducted in the period of November ane, 2018, to May 31, 2020. All documents were analysed past ii researchers independently.

Results

Xx-four CECCs were requested within the study period, of which almost (n = 22; 92%) had been initiated by physicians of the department. The patients were an average of 79 years old (R: 43–96), and xiv (58%) patients were female person. The median length of stay prior to request was 12.five days (R: 1–65 days). The most frequent diagnoses (several diagnoses possible) were cardiology-related (due north = 29), followed by sepsis (north = 11) and cancer (due north = six). 20 patients lacked decisional capacity. The main reason for a CECC request was doubt about the balancing of potential benefit and impairment related to the medically indicated treatment (n = eighteen). Further reasons included differing views regarding the best individual treatment option betwixt health professionals and patients (n = iii) or between different team members (due north = 3). Consensus between participants could be reached in xviii (75%) consultations. The implementation of a affliction specific handling intervention was recommended in 5 cases. Palliative care and limitation of further affliction specific interventions was recommended in 12 cases.

Conclusions

To the best of our cognition, this is the first in-depth evaluation of a CECC service fix for an bookish section of cardiology and intensive medical care. Patient characteristics and the issues deliberated during CECC provide a starting indicate for the development and testing of more than tailored clinical ideals support services and enquiry on CECC outcomes.

Background

Care of patients with cardiovascular disorders poses regular upstanding challenges, especially due to advanced age, cognitive deficits, frailty or multimorbidity [i, 2]. The identification and estimation of advance stated or presumed preferences regarding potential cardiological handling are among the more frequent ethical challenges. Furthermore, ethical problems form part of decisions about treatment indication in the form of weighing the potential do good of a cardiovascular intervention against risks of potential harm. Practical examples of this type of clinical-ethical challenge are the deactivation of the shock part of an implanted defibrillator in a patient with hypoxic brain damage after resuscitation [three, 4] or transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with advanced historic period, cerebral deficits and symptomatic aortic valve stenosis. In the latter case, for example, the risks associated with the intervention accept to be evaluated confronting the benefits, including improvement of the cognitive status subsequently transcatheter aortic valve implantation [v,6,7].

The relevance of ethical issues in everyday clinical practise is well-documented by several international studies [viii,9,10,eleven]. The latter betoken that ethical challenges tin have negative furnishings, such as moral distress for those involved [4, 12,13,14,15]. Clinical ideals case consultation (CECC) services take been introduced in many hospitals and other healthcare institutions to provide a systematic and comprehensive assay of ethical challenges related to patient care in the case of ethical uncertainty or moral conflicts [16,17,18,19,20]. Different models of CECCs be, still, there are some mutual features, which are summarised in Box 1.

While the possible value of CECC for clinical practice has been stated in numerous publications, there is withal little evaluation enquiry related to CECCs [22,23,24]. Evaluating CECCs by means of empirical methods is important for several reasons. The get-go is that evaluation may further promote the transparency and accountability of CECCs and those offering this service. A 2d reason is the potential impact of the results of such studies on the quality of the service. If, for example, service users are dissatisfied with the time which elapses from asking to the actual provision of a CECC, this attribute may be reconsidered past CECC providers. A 3rd reason which tin be forwarded for the evaluation of outcomes of ethics consultation is that such inquiry may stimulate reflection on the provision of consistent CECC services [23,24,25].

Little is known so far about the characteristics of CECCs provided within cardiovascular medicine. At the same time, patients with cardiovascular diagnoses frequently give rise to clinical ethics consultation [26,1,2,3,four,5,six,7,8,9,10,xi,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,nineteen,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. This is particularly true for CECCs taking identify in intensive care [21, 23]. Information almost CECCs in specific clinical contexts is relevant to be able to develop tailored interventions which fit the clinical setting and the needs of patients and health professionals in a particular field of medicine. In add-on, such data tin inform future evaluation inquiry on the outcomes of CECCs, for example, by pointing out relevant criteria to measure potential benefits or harms of the intervention [21]. Confronting this groundwork, this paper presents findings of an in-depth descriptive analysis of clinical ideals consultation, conducted past a CECC service, which was set up jointly by clinical ethicists and cardiologists in a German university hospital in Nov 2018. The aims of this study are

- 1.

To explore the upstanding issues underlying requests for CECCs in a cardiology section at a German university hospital.

- 2.

To provide descriptive evaluation data on the content and recommendations of CECCs conducted for patients suffering from cardiovascular diseases, and health professionals.

Methods

We performed a retrospective document analysis of protocols which were the documented results of CECCs conducted in our department of cardiology and intensive care unit of measurement for the period November 2018 to May 2020.

Setting

The report took place in the cardiology clinic of Academy Hospital Halle in Germany. The university infirmary is a supraregional maximum care provider with 32 clinics/departments with 982 beds. Approximately 40,000 inpatient and 195,000 outpatient treatments are performed per year. The main focus of the University Hospital is on cardiovascular diseases and oncology. The cardiology clinic of the infirmary has a ward with 60 beds and an intensive care unit with 25 beds. The medical and nursing squad is staffed by: 75 nurses and 60 physicians. The University Hospital has an ethics committee with 35 members from various areas of medical and not-medical care. Membership is honorary. One member is employed on a half-fourth dimension basis to organise the work of the commission as a managing director. A subgroup of the committee (ethics squad) located in the Institute for History and Ideals of Medicine conducts CECC services in the cardiology clinic.

Intervention

The ethics team is equanimous of 2 medical ethicists (with backgrounds in philosophy and medical law), a physician (internist and oncologist) and a lawyer (on a demand basis), who have been trained in CECC according to national recommendations [29, 30]. In Federal republic of germany, CECCs have shown difficulties in getting established or rather getting cases in clinical settings. Therefore, adjacent to ethics consultations performed on request the ideals team and the cardiology department agreed that prompting ethics consultations through a regular weekly reminder was deemed a practiced measure to remind the health professionals and to reflect on, whether there was a example, which should be discussed every bit office of CECC.

Thus, the CECC service comprises two modes of initiation:

- I.

Weekly contact initiated by the clinical ethicist with a senior cardiologist to determine whether there is a possible case for ideals consultation.

- II.

Ethics consultation on request past members of the cardiology team or by the patients, relatives or surrogates in case of need.

The weekly request (I) is characterised past a standardized e-mail request sent past the committee manager to the same senior cardiologist at the same fourth dimension each calendar week asking if there is a demand for consultation. The senior cardiologist explores whether there is a need for consultation in the regular team meetings with the other senior physicians, who forward the question to the ward team (top-downwards principle). The requests are bundled and sent to the senior cardiologist, who so frontwards them to the ethics team.

Spontaneous inquiry (Ii) is possible at whatsoever fourth dimension by any staff member of the dispensary, and by patients and their relatives. Information and contact details are bachelor on every ward of the hospital (bottom-up principle). Requests tin be fabricated informally at any time.

The ethics team can be contacted via telephone, an emergency cell phone, email or the patient management organisation. At to the lowest degree i and a maximum of iii consultant(south) from the ethics team will participate in each consultation. The selection of team members for each case is based on time capacity and experience with the subject matter. If hard legal issues are identified in advance, the participation of a lawyer is offered. The commission managing director participates in each consultation. Subsequent to both ways of initiating a CECC, a first meeting betwixt a consultant, physicians and nurses of the corresponding ward volition be arranged by the commission managing director ordinarily within 24 h of the request. This session takes place on the patient'due south ward and follows a structured procedure, which is illustrated in Box 1. The initial session ordinarily takes nigh twenty–45 min. In addition, the ethics consultant visits the patient and eventually proxies or relatives to elicit and hash out her or his preferences and values regarding the questions at stake if possible. Furthermore, cases are always discussed between at least two members of the ethics team. One-half-yearly debriefings of selected cases are held with the ethics commission for quality assurance purposes.

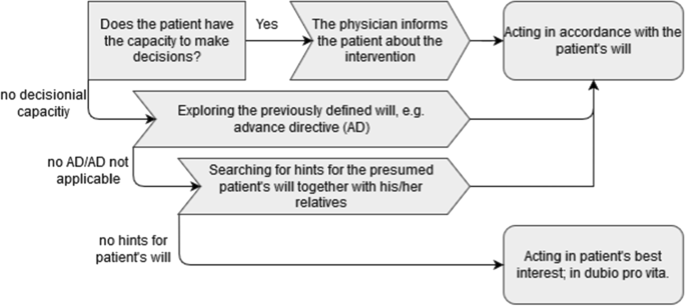

The respective indication (one) and the patient'due south will (ii) equally a representation of autonomy are the focus of the CECC. Regarding the indication, the main task of the CECC is to place the rationale for offering (or limiting) diagnostic and/or therapeutic procedures with a focus on the value judgments underlying the formulated goal of care and the weighing of benefits and harms. If a treatment is not or no longer indicated from a medical bespeak of view, it is non permissible nether German police and must be discontinued. However, a large number of publications in Frg bear witness different definitions of the term medical indication, leading to upstanding uncertainties in practice [31,32,33]. Merely treatments that are actually indicated may be offered to the patient for consent. Therefore, the patient'south will regarding possible treatments is limited to those treatments indicated. Informed consent is legally and ethically required in Germany for all medical treatments. The legal requirements for the patient to exist able to give informed consent are that he or she has the capacity to give consent (decisional capacity). This means that the patient is able to sympathize the significance and scope of the medical intervention, evaluate the pros and cons, and communicate the decision. It is the chore of the attending medico to determine this [34]. If the patient is not competent, a proxy must give informed consent for him/her based on the patient's volition [undefined]. Regarding the evaluation of the patient's volition, the procedural steps are summarised in Fig. one.

Schematic summary of the procedural steps regarding evaluating the patient'southward will as part of the CECC

If necessary, the ethics consultant, in collaboration with further stakeholders of the process, initiates farther steps, such as additional discussions with the patient'south representatives, the nursing habitation staff, or the interest of relevant specialists (e.1000. cardiac surgery, geriatrics, palliative care). In improver, legal advice from experts in medical constabulary is sought if required. Subsequent to the ideals consultation process, a draft summary including the recommendations of the clinical ethics team is sent to the healthcare team for comments and it is documented in the patients' record after completion. This is, firstly, to make the conversation and the recommendations transparent and, secondly, to forestall misunderstandings related to identified, ethically relevant just also clinical issues. The attention physician informs the patient (if possible) and his or her relatives or legal representatives, if they were not nowadays at the consultation, of the contents and recommendations of the CECC. The possibility of a renewed discussion is always offered. Access to the medical record and the CECC protocol by the patient or the patient's proxy is always guaranteed.

Data cloth and assay

A semi-standardized protocol normally comprising two to v pages, was used for the documentation of each case. Information technology consists of (a) the patient's name, (b) a list of important relatives, (c) a list of members of the treatment team, (d) the ethical question(southward), (e) diagnoses, (f) medical-nursing aspects, (thousand) the patient's will/decisional chapters, (h) the procedure(s) discussed or medically indicated and (i) the CECC recommendations. Furthermore, we had data on the duration of the consultation, time from request to recommendation, and time from recommendation to belch. Data was anonymized regarding the names of the CECC participants. All protocols from November 2018 to May 2020 were analysed.

We descriptively analysed diagnoses, the condition (i.due east. professional, patient, relative) of the requester of the CECC, the profession of the CECC participants, the clinical (ward, decisional capacity, length of stay) and patient'due south socio-demographic characteristics (historic period, gender), the duration of consultation, the time from asking to recommendation and the time from recommendation to discharge. We report the data with accented and relative frequencies and the median and minimum to maximum ranges because the data were non normally distributed.

To exist able to elicit also more implicit aspects of CECC we employed a structured qualitative content analysis approach based on hermeneutics [36]. 2 researchers, one with a background in medical ethics (AN) and the other in philosophy (NH), inductively coded the kickoff eight protocols independently and derived a category system for the ethics questions, decisional capacity, the patient's volition and recommendations. In add-on to small wording differences, the researchers had formed identical categories because the densely written protocols left footling room for interpretation. The categories were, therefore, briefly discussed in the enquiry team and, subsequently, the remainder of the cases were coded. No further codes were necessary in the process. MAXQDA 2020 was used for the analysis. Due to the lack of interpretative depth, the categories were reported quantitatively with accented and relative frequencies. See Table 1 for information on the coding for the quantitative reporting. Additionally, we use summarised case descriptions equally examples to illustrate the CECC process.

Results

Thirty-7 consultations took identify throughout the entire academy hospital during the report period. Of the 37 consultations, 24 (64.86%) were requested by the cardiology clinic and were, thus, included in the document analysis. Xviii inquiries resulted from the regular weekly contact betwixt the ideals consultant and the senior doc of the department. A CECC was requested by one of the wards of the section in a further 6 cases. The CECCs were initiated by physicians of the department in 22 cases, one time by a full general practitioner of the patient and in one case past a relative of the patient. The time betwixt asking and initial meeting between the ethics consultant and a member of the healthcare squad was less than 24 h, with two exceptions. The median time of the CECC from the initial meeting to the recommendation was 1 day (R: 0–7 days). Two patients died prior to the initial coming together and one patient discharged himself confronting medical communication prior to the consultation.

Physicians were involved in all cases during the CECC process, which encompassed i to iv meetings with unlike stakeholders including the patient. Nurses of the ward participated in eighteen cases and physicians of other disciplines (geriatrics [n = 2], palliative care [n = 2], oncology [northward = 1]) participated in 5 cases. The patient'southward relative(s) were involved in 13 cases, of which viii were legal representatives of the patient. In half dozen cases, the patient was represented by a professional person legal guardian. In 2 cases, the staff of the nursing home where the patient lived were contacted to obtain relevant information.

Medical, socio-demographic information and procedural aspects

At the time of the CECC, 13 patients (54.two%) had been treated on a general ward, and eleven patients (45.8%) on an intensive or intermediate care unit, respectively. 14 patients (58%) were female, and the median age was 79 years (R: 43–96). Twenty patients (83%) were lacking decisional capacity continuously, and the decisional capacity one time was fluctuating. In seven of these 21 cases, verbal advice was possible but these patients were accounted non to be able to make a decision according the requirements of decision capacity. The median length of stay prior to request was 12.5 days (R: i–65 days). Table 2 provides an overview of the length of stay and CECC-related milestones.

The diagnosis leading to infirmary admission was a cardiovascular illness in 14 cases (58%). Cardiology-related diagnoses were the most frequent main diagnoses (northward = 29), followed by sepsis (northward = eleven) and oncological diseases (north = 6) (multiple diagnoses possible). The bulk of patients were characterised past multimorbidity. As a result, even supposedly trivial diagnoses in combination with the other diagnoses could lead to circuitous situations regarding clinical decision-making.

Reasons for the request and content of CECC

Reasons for asking

Dubiousness virtually the balancing potential of benefit and damage related to the medically indicated treatment was the main reason for a CECC asking in north = 18 (75%) cases (multiple reasons possible). Factors contributing to the uncertainty were advanced age, express life expectancy, multimorbidity and frailty (according to the clinical judgment). Incongruent perspectives of the relatives and ward staff regarding the choice of treatment were the reason for the initiation of a CECC asking in many cases (n = 16). Furthermore, differing views between wellness professionals and patients (n = three) or between different team members (n = three) concerning the all-time individual treatment option led to a CECC. One further reason was the dubiety of the treatment team, relatives and/or proxies regarding the patient's supposed will regarding a detail intervention in the case of lacking capacity (n = vi). Additional challenges leading to CECC requests were situations in which no close relatives of the patient could exist located or the statements of the corresponding patient and/or the relatives were incongruent.

The following case summary provides an example of a typical scenario leading to a request for CECC.

Example Protocol Y7:

An 84-year-old female patient was resuscitated outside the hospital. From this time on, she had to be ventilated. A tracheotomy and a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube are medically indicated to ensure long-term ventilation and diet. The patient's two sons and one girl-in-constabulary brand contradictory statements regarding the mother'due south presumed will. A legal guardian has been appointed for the patient. He does not know the patient and does not feel able to make this decision. A CECC was requested to support the elicitation of the patient's (presumed) will in calorie-free of the treatment options offered and related goals of care. In club to find out more than nigh the patient'southward will, the CECC suggested contacting the patient's nursing home and the nurse who had been caring for the patient for years.

Content of the CECC

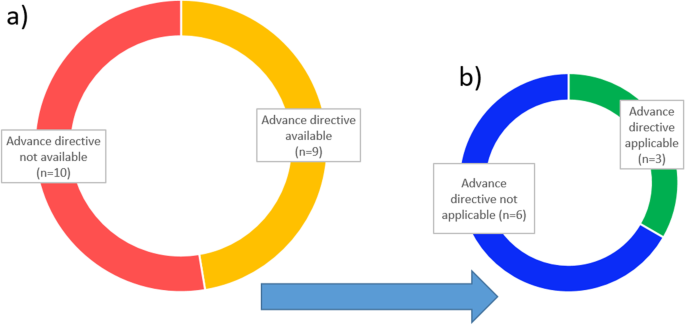

In accordance with the method utilised in the CECC, the analysis of protocols showed that the centre of discussion during the CECC was most oft the patient's volition, on the one paw, and the rationale for medical indication, in particular the benefits and harms of treatment as evaluated by the healthcare team, on the other hand. Advance directives were available regarding the offset pillar of ethical determination-making in ix cases. In the latter, life-sustaining treatments, such as artificial respiration and resuscitation, were refused. However, these orders were always linked to specific situations or presumed treatment outcomes (due east.g. permanent severe demand for care or irreversible brain damage). In three of these cases, advance directives were directly applicative to the situation (run across Fig. two). In six of the nine advance directives, the state of affairs or outcome described could non be identified with certainty past the handling squad. In these cases, the patient'due south will had to exist clarified via other sources (run across Fig. 1). The not-applicable advance directives were included in the considerations when determining the patient's (presumed) will. In all cases in which a patient was deemed to have no decisional capacity, handling options were discussed with the patient as far as feasible.

Summary of the function of accelerate directives in the CECC. a Availability of an advance directive for patients incapable of consenting during the CECC (excluding two patients deceased before consultation). b Evaluation of the applicability of the existing advance directives to the specific situation regarding CECC participants

The CECC focused more often than not on the balancing of (presumed) benefit and harm in discussions virtually the medical i ndication, as a prerequisite for any offering of a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure. Based on an explicit discussion of value judgments in the context of the medical indication, the handling options considered were withdrawn in three cases because in that location was no longer an indication due to various characteristics of the patients. This may be the example if, for example, prolongation of life past handling no longer seems possible from a medical signal of view due to the multimorbidity overall condition of the patient. Alternatively, the risk of dying before as a result of the treatment is much higher than the possibility of prolonging life by the treatment. The following instance summary provides an illustrative instance for such a scenario.

Example Protocol N2:

A patient with dehydration, severe hypernatremia, advanced dementia and an autoimmune skin illness that has besides spread into the oral cavity refuses to swallow and take oral medication. The treatment team considers the placement of a PEG tube is indicated. In the course of the CECC, a geriatrician was consulted who pointed out that the refusal of oral intake was uniform with the advanced country of dementia. Furthermore, information technology was stated that the application of a PEG tube at this stage of dementia, likewise based on existing recommendations in guidelines, was deemed to be contraindicated due to a lack of benefit and the associated potential harm of the procedure for the patient at this avant-garde stage of the disease. Equally a result of the CECC, the placement of PEG was not further deemed as indicated in the corresponding patient.

Recommendations as an outcome of the CECC process

According to the CECC protocols, consensus between participants could exist reached in 18 out of 24 consultations (75%). The dissent could non be resolved in 3 cases. Two patients died before a final recommendation could be reached and one patient discharged himself prior to completing the CECC procedure. Recommendation usually included practical steps relevant to farther care and handling. The implementation of a disease-specific handling intervention was recommended in five cases. A confirmation of palliative care and limitation of further affliction-specific interventions was the therapeutic goal recommended by the CECC in 12 cases. The CECC squad decided on a 'freezing' of the current treatment with a re-evaluation in the most hereafter in iv cases (come across Table 3).

Recommendations were based by and large on the (presumed) will of the patient. The absence of evidence of the patient'southward will in two cases led to the recommendation to perform life-saving treatment (in dubio pro vita). Recommendations were based on the lack of medical indication in four cases, following a word during the CECC with participating health professionals regarding the benefits and harms of possible technical interventions.

Example Protocol T6:

A 54-year-old patient with hypoxic brain damage afterwards about 45 min of cardiopulmonary resuscitation with still unclear neurological prognosis. The treatment squad is uncertain whether continuation of intensive care handling is in accord with the patient'south volition. The patient relies on mechanical ventilation. A legal representative could just locate the patient's sis, who had non had contact with the patient for years and could not provide reliable data about the patient's volition. Due to the lack of data about the patient'due south will, the continuation of medically indicated life-sustaining handling was recommended by the CECC.

The analysis of the protocols showed no differences regarding the points presented between the consultations initiated by the weekly prompts by the ethics team and those from requests from the members of the cardiology team.

Give-and-take

This paper provides an in-depth descriptive analysis of CECCs in cardiology and intensive intendance in internal medicine. To the best of our knowledge, this is the showtime publication with qualitative and quantitative data elicited from CECC protocols from an academic section of cardiology and intensive care. In the post-obit we will discuss the findings with a focus on the common reasons for CECC requests in cardiology, procedural aspects of the CECC service provided, and implications for the development of more tailored clinical ethics support interventions and respective evaluation research.

Requests for CECCs in cardiology and intensive care

The requests for CECCs reflect the technical possibilities provided by modern cardiology and intensive care and the associated uncertainty most the benefits and harms of the medical interventions available in a subgroup of patients characterised by advanced historic period, limited life expectancy, multimorbidity and frailty. Given these challenges associated with decisions about the offering of specific interventions, it is non surprising that the majority of CECC requests were made by physicians involved in the treatment of patients. By contrast, but few requests had been made by nurses or patients' representatives or relatives. The reasons for this may be the focus of the CECCs on ethical problems related to decisions well-nigh the medical treatment and less near ethical challenges related to nursing care. In add-on, in that location may exist a low public awareness of CECCs or a lack of information virtually CECCs in the department [8, 37,38,39]. Furthermore, due to the specific arroyo of contacting a senior cardiologist on a weekly basis, most CECCs occurred equally a result of prompting the physicians with a question about a possible need for a CECC. The fact that most consultations stem from regularly prompts on behalf of the CECC team may point to the potential of such initiatives to increase the sensation of ethics bug [xl,41,42] and, subsequently, increase the number of CECCs [43]. Given data on the experience of nurses with ethical challenges [44,45,46], ane complementing strategy could be a joint weekly phone call with a senior nurse to include this professional perspective as well.

Clinical-ethical bug in CECCs provided to cardiology and intensive intendance

Our analysis reveals that, comparable to other studies, CECCs in cardiology and intensive care focused on eliciting the patient's will and the balanced multidisciplinary word of potential benefits and harms [23, 24, 47]. Our findings suggest that there was oft no dispute almost facts but almost the judgement of pivotal issues related to the private instance (i.e. considering avant-garde age, multimorbidity, frailty, residual quality of life and limited life expectancy). If this value judgement is incorporated implicitly into the supposedly objective medical view, there is a risk that a patient may be deprived of decisions which take into account personal values. In this respect, our analysis shows that i of import part of a CECC was to brand explicit value judgments regarding (presumed) benefits and harms [48]. It is important here to distinguish damage and benefit viewed by health professionals and evaluations in this respect on side of the patient. In line with a principle based approach [49] nosotros would argue that health professionals do take a job to evaluate do good and harm but must be clear about their evaluation too as the reference indicate for the judgement. Ane such reference point are considerations according to the "best interest" [l] of the patient. This is also an important legal signal. If a therapy is discontinued due to a lack of indication, this may but happen based on medical considerations but non on the basis of considerations on the part of the treatment team regarding their values. If the medical indication is given, it is the patient's values and wishes, which are decisive about whether the treatment is taking place or not. During the process of deliberation offered past a CECC, participants were able to exchange their perceptions and views and effort to find a mutual ground. In parts of the cases, interest of disciplines outside cardiology contributed to an informed weighing of benefits and harms. In this instance, the CECC provided a forum for deliberation about all options medically available, ranging from disease-specific advanced cardiovascular interventions to palliative care. As evidenced by our assay, in the case of uncertainty almost a patient's will and the balancing of benefits and harms, an 'in dubio pro vita' approach was called. Furthermore, the alter to palliative intendance goals as a upshot of CECC discussions reflects that cardiology and intensive care might benefit from models of early palliative care, which have already been established in some leading centres for patients with heart failure [51,52,53].

Fourth dimension and procedural characteristics of the CECC service in cardiology and intensive care

Our data show that clinical-ethical uncertainties were usually resolved and a consensus reached within an boilerplate of 48 h. In contrast to the prejudice that the CECC is too time-consuming [eight, 54], our results instead point to the fact that the CECC can facilitate a swift process in otherwise time-consuming decision-making processes characterised by delays due to dissent and doubtfulness [22]. In light of the known substantial increase of the workload in cardiology and intensive care [55], handling of communications and appointments with the patients' relatives or legal guardians and the documentation process of the CECC undertaken by ethics professionals might aid in relieving the cardiovascular and intensive care specialists from these time-consuming activities. However, a critical reflection on the CECC in an environment with a high instance load and time constraints in cardiology is still of import. Time is a crucial but also ambivalent factor in the joint decision-making procedure of CECCs. Waiting for the development of a wellness status during an already initiated intensive treatment, for example, can provide a better foundation for the prognosis simply, at the same fourth dimension, can place an increased brunt on the treatment team, the relatives and, last but not least, the patient [56].

A procedural characteristic of the CECC provided is the close collaboration of the ethics consultants with experts in medical law. Such a collaboration provides several advantages: firstly, it creates legal certainty for the consultation by eliminating unlawful options and clarifying the legal framework within which to operate. Secondly, it adds another perspective to the determination of the patient's (presumed) will, non simply by laying out the legal guidelines for this decision and the requirements for advanced directives merely also by providing assist for the estimation of the patient's statements. While the final decision and the (legal) responsibility remains with the treating physician, articulation ethico-legal consultation can aid to forbid legal conflicts that eventually might besides accept an touch on the treatment of the patient.

Possible implications for a tailored CECC and evaluation

The preceding assay points to more general only also more specific features of CECCs in a university cardiology department, which may serve as a starting point for the evolution of more tailored CECC interventions and suitable upshot criteria. The comparison of the number of CECCs from the cardiology clinic, the merely clinic where the proactive weekly asking was implemented, with the residue of the university hospital (without a proactive arroyo) suggests that weekly inquiries may besides lead to an increased use of the ethics offer. This could be due to the fact that this regularly draws attention to the offer. Another signal could also be that the involvement of leading personnel (such as a senior physician in our study) could pb to a higher acceptance of CECCs by the rest of the team. On the part of the consulting team, special attention must be focused on avoiding an authorisation bias. Regarding the intervention, the length of time prior to a request for a CECC raises the question whether more than proactive interventions, for example, inside the context of usual ward rounds, may facilitate an before analysis of upstanding and sometimes legal bug. This is particularly the case given the loftier proportion of patients lacking decisional capacity in our sample. Handling of these patients regularly begs questions regarding presumed or advance stated will and weighing benefits and harms from a professional perspective. Advance directives tin can help to tape the patient's will for future situations and the need for consideration by relatives or the treatment team. Unfortunately, our inquiry shows — similar to other studies (for a review see Fagerlin and Schneider [57]) — that advance directives often neglect to take an effect in practice. Ane reason for this is that they are ofttimes not applicable to the specific situation. This can ofttimes be the reason for ethical issues. The implementation of an accelerate care planning offering could annul these challenges in the future every bit a kind of a preventive ethics offer in hospitals. 1 further aspect of future more tailored interventions are shorter and more focused elements of ethics support instead of the provision of a comprehensive CECC which often takes upward to one 60 minutes of time involving several health professionals. A time investment which needs to exist justified in light of competing tasks which benefit patients. Reflections of modifications regarding CECC services should be likewise aligned with considerations regarding adequate evaluation criteria. In this respect, a detailed descriptive account of procedurals steps of unlike modes of ideals support, related goals and expertise which are contributed past ways of a particular CECC service is a prerequisite [21]. Furthermore and in lite of the findings of this descriptive study, the more specific features of CECCs in cardiology should be taken into account when defining appropriate evaluation criteria. Possible candidates for such context-specific features are the range of technical measures and interventions offered every bit part of cardiology care and the challenges associated with prognosis and different end-of-life trajectories in this field of medicine.

Limitations

The CECCs reported were performed with a limited number of cases simply at a single centre, therefore, results are per se not generalizable. However, our results regarding the upstanding issues and requests are similar to those of other studies [28, 58, 59] and add together to our knowledge on CECCs in the detail setting of cardiology and intensive care. We based our analysis simply on retrospective protocol data and, thus, we cannot a) make up one's mind the overall of quality of the CECCs performed since document analysis solitary is hardly capable of reflecting all levels of quality, and b) infer house causal conclusions between CECCs and possible outcomes. Furthermore, our analysis may have been influenced by data interpretation bias since ii of the authors are members of the CECC team. We tried to increment trustworthiness of the assay through the reporting of 'negative' findings, for case, dissent at the end of a CECC, illustration through example summaries and discussion of the results in the research team. The protocols analysed were outcome protocols and, therefore, already written very densely and briefly, leaving little room for estimation in terms of coding.

Conclusions

The combination of a range of technical interventions and a subgroup of patients with advanced age, multimorbidity and frailty is 1 trigger for upstanding uncertainty and conflicts in cardiology and intensive care. A CECC tin be a viable intervention in facilitating word on these bug between different stakeholders with and on behalf of the patient. The timely initiation of ideals consultation through direct contact with a senior cardiologist proved to be a good strategy to enhance upstanding issues in daily cardiology practice and could exist extended to contact with nursing staff. The evaluation of this intervention based on document analysis can give a kickoff insight into the topics, processes and quality of CECCs. Farther analysis with mixed-methods approaches and different sources is needed to gain a clearer film of the quality domains of the structure, process and outcome and the tailoring of CECC interventions in cardiology.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality reasons but are available from the corresponding writer on request.

References

-

Cameron AAC, Laskey WK, Sheldon WC. Ethical issues for invasive cardiologists: society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;61:157–62. https://doi.org/ten.1002/ccd.10800.

-

Vincent J-L. Ethical problems in cardiac arrest and acute cardiac care: a European perspective. In: Tubaro One thousand, Vranckx P, Price S, Vrints C, editors. The ESC textbook of intensive and acute cardiovascular intendance. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. p. 91–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199687039.003.0013_update_003.

-

Pullman D, Hodgkinson Thousand. The curious case of the de-ICD: negotiating the dynamics of autonomy and paternalism in complex clinical relationships. Am J Bioeth. 2016;16:three–ten. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2016.1187211.

-

Steiner JM, Patton KK, Prutkin JM, Kirkpatrick JN. Moral distress at the finish of a life: when family unit and clinicians do non agree on implantable cardioverter-defibrillator deactivation. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55:530–4. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.11.022.

-

Ak A, Porokhovnikov I, Kuethe F, Schulze PC, Noutsias M, Schlattmann P. Transcatheter vs. surgical aortic valve replacement and medical treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and not-randomized trials. Herz. 2018;43:325–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-017-4562-5.

-

Auffret V, Campelo-Parada F, Regueiro A, Del Trigo M, Chiche O, Chamandi C, et al. Serial changes in cognitive function following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2129–41. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.046.

-

Huber H, Stocker R. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in elderly patients: shared conclusion making betwixt medical indication and social demand. Z Med Ethik. 2020;66:403–19.

-

DuVal G, Clarridge B, Gensler Yard, Danis K. A national survey of U.S. internists' experiences with ethical dilemmas and ethics consultation. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:251–8. https://doi.org/x.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21238.x.

-

Hurst SA, Perrier A, Pegoraro R, Reiter-Theil South, Forde R, Slowther A-G, et al. Ethical difficulties in clinical practice: experiences of European doctors. J Med Ethics. 2007;33:51–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2005.014266.

-

Rainer J, Schneider JK, Lorenz RA. Ethical dilemmas in nursing: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:3446–61. https://doi.org/x.1111/jocn.14542.

-

Wiegand DL, MacMillan J, dos Santos MR, Bousso RS. Palliative and stop-of-life ethical dilemmas in the Intensive Care Unit of measurement. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2015;26:142–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCI.0000000000000085.

-

Huffman DM, Rittenmeyer L. How professional person nurses working in hospital environments experience moral distress: a systematic review. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;24:91–100. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.ccell.2012.01.004.

-

Lamiani G, Borghi L, Argentero P. When healthcare professionals cannot practise the right thing: a systematic review of moral distress and its correlates. J Health Psychol. 2017;22:51–67. https://doi.org/x.1177/1359105315595120.

-

McCarthy J, Gastmans C. Moral distress: a review of the statement-based nursing ethics literature. Nurs Ethics. 2015;22:131–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014557139.

-

Oh Y, Gastmans C. Moral distress experienced by nurses: a quantitative literature review. Nurs Ethics. 2015;22:15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013502803.

-

Fob E, Myers Due south, Pearlman RA. Ideals consultation in Usa hospitals: a national survey. Am J Bioeth. 2007;seven:13–25. https://doi.org/ten.1080/15265160601109085.

-

Gather J, Kaufmann S, Otte I, Juckel G, Schildmann J, Vollmann J. Level of development of clinical ethics consultation in psychiatry: results of a survey among psychiatric acute clinics and forensic psychiatric hospitals. Psychiatr Prax. 2019;46:90–half dozen. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0579-6469.

-

Hurst SA, Reiter-Theil S, Perrier A, Forde R, Slowther A-K, Pegoraro R, Danis M. Physicians' admission to ethics back up services in four European countries. Health Care Anal. 2007;fifteen:321–35. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s10728-007-0072-6.

-

Schochow One thousand, Schnell D, Steger F. Implementation of clinical ethics consultation in German hospitals. Sci Eng Ethics. 2019;25:985–91. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s11948-015-9709-2.

-

Slowther AM, McClimans Fifty, Toll C. Evolution of clinical ethics services in the Uk: a national survey. J Med Ideals. 2012;38:210–4. https://doi.org/x.1136/medethics-2011-100173.

-

Schildmann J, Nadolny Due south, Haltaufderheide J, Gysels Yard, Vollmann J, Bausewein C. Do nosotros understand the intervention? What complex intervention research can teach usa for the evaluation of clinical ethics support services (Assessment). BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20:48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-019-0381-y.

-

Chen Y-Y, Chu T-Due south, Kao Y-H, Tsai P-R, Huang T-S, Ko W-J. To evaluate the effectiveness of health care ethics consultation based on the goals of health intendance ideals consultation: a prospective cohort study with randomization. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-15-one.

-

Haltaufderheide J, Nadolny S, Gysels M, Bausewein C, Vollmann J, Schildmann J. Outcomes of clinical ideals back up most the end of life: a systematic review. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27:838–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019878840.

-

Schildmann J, Nadolny S, Haltaufderheide J, Gysels One thousand, Vollmann J, Bausewein C. Ethical case interventions for adult patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7:CD012636. https://doi.org/x.1002/14651858.CD012636.pub2.

-

Williamson L. Empirical assessments of clinical ideals services: implications for clinical ethics committees. Clin Ethics. 2007;2:187–92. https://doi.org/10.1258/147775007783560184.

-

Andereck WS, McGaughey JW, Schneiderman LJ, Jonsen AR. Seeking to reduce nonbeneficial treatment in the ICU: an exploratory trial of proactive ethics intervention. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:824–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000034.

-

Löbbing T, Carvalho Fernando S, Driessen M, Schulz K, Behrens J, Kobert KKB. Clinical ethics consultations in psychiatric compared to not-psychiatric medical settings: characteristics and outcomes. Heliyon. 2019;5: e01192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01192.

-

Swetz KM, Crowley ME, Hook C, Mueller PS. Report of 255 clinical ethics consultations and review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:686–91.

-

Akademie für Ethik in der Medizin e.Five. Curriculum Ethikberatung im Gesundheitswesen. 2019. https://world wide web.aem-online.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Curriculum_Ethikberatung_im__Gesundheitswesen_2019-06-24.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2020.

-

Standards für Ethikberatung in Einrichtungen des Gesundheitswesens. Ethik Med. 2010;22:149–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00481-010-0053-4.

-

Lipp 5. Die medizinische Indikation – ein "Kernstück ärztlicher Legitimation"? MedR. 2015;33:762–half-dozen. https://doi.org/x.1007/s00350-015-4126-8.

-

Wiesing U. Indikation: Theoretische Grundlagen und Konsequenzen für die ärztliche Praxis. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag; 2017.

-

Dörries A, Lipp V, editors. Medizinische Indikation: Ärztliche, ethische und rechtliche Perspektiven; Grundlagen und Praxis. 1st ed. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer; 2015.

-

Deutsch E, Spickhoff A. Medizinrecht: Arztrecht, Arzneimittelrecht, Medizinprodukterecht und Transfusionsrecht. 7th ed. Berlin: Springer; 2014.

-

Borasio GD, Heßler H-J, Wiesing U. Patientenverfügungsgesetz: Umsetzung in der klinischen Praxis. Dtsch Arztebl. 2009;xl:1952–7.

-

Kuckartz U. Qualitative text analysis: a guide to methods, exercise & using software. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2014.

-

Gacki-Smith J, Gordon EJ. Residents' access to ethics consultations: noesis, use, and perceptions. Acad Med. 2005;fourscore:168–75. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200502000-00014.

-

Gaudine A, Lamb M, LeFort SM, Thorne L. Barriers and facilitators to consulting hospital clinical ideals committees. Nurs Ethics. 2011;xviii:767–lxxx. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733011403808.

-

Orlowski JP, Hein S, Christensen JA, Meinke R, Sincich T. Why doctors use or practise not use ideals consultation. J Med Ideals. 2006;32:499–502. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2005.014464.

-

Bruun H, Huniche L, Stenager E, Mogensen CB, Pedersen R. Infirmary ethics reflection groups: a learning and development resource for clinical practice. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;twenty:75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-019-0415-five.

-

Silén M, Ramklint M, Hansson MG, Haglund K. Ethics rounds: an appreciated form of ideals back up. Nurs Ideals. 2016;23:203–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014560930.

-

Svantesson M, Lofmark R, Thorsen H, Kallenberg K, Ahlstrom G. Learning a mode through upstanding problems: Swedish nurses' and doctors' experiences from one model of ideals rounds. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:399–406. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2006.019810.

-

van der Dam S, Molewijk B, Widdershoven GAM, Abma TA. Ethics support in institutional elderly intendance: a review of the literature. J Med Ideals. 2014;40:625–31. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2012-101295.

-

Bartlett VL, Finder SG. Lessons learned from nurses' requests for ideals consultation: why did they call and what did they value? Nurs Ethics. 2018;25:601–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733016660879.

-

Gaudine A, LeFort SM, Lamb M, Thorne L. Ethical conflicts with hospitals: the perspective of nurses and physicians. Nurs Ideals. 2011;18:756–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733011401121.

-

Gaudine A, LeFort SM, Lamb G, Thorne L. Clinical upstanding conflicts of nurses and physicians. Nurs Ethics. 2011;xviii:9–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733010385532.

-

Haan MM, van Gurp JLP, Naber SM, Groenewoud AS. Bear on of moral case deliberation in healthcare settings: a literature review. BMC Med Ideals. 2018;19:85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0325-y.

-

Wocial LD, Molnar E, Ott MA. Values, quality, and evaluation in ideals consultation. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2016;7:227–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2015.1127295.

-

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. New York: Oxford Academy Press; 2019.

-

Bester JC. The best interest standard and children: clarifying a concept and responding to its critics. J Med Ethics. 2019;45:117–24. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2018-105036.

-

Lewin WH, Schaefer KG. Integrating palliative care into routine care of patients with heart failure: models for clinical collaboration. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22:517–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-017-9599-2.

-

Schildmann J, Nadolny South, Buiting HM. What do we mean by "palliative" or "oncologic intendance"? Conceptual clarity is needed for audio inquiry and skilful care. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2814–v. https://doi.org/ten.1200/JCO.20.00658.

-

Radbruch L, de Lima L, Knaul F, Wenk R, Ali Z, Bhatnaghar S, et al. Redefining palliative care: a new consensus-based definition. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2020;60:754–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027.

-

Forde R, Pedersen R, Akre Five. Clinicians' evaluation of clinical ideals consultations in Norway: a qualitative report. Med Health Intendance Philos. 2008;11:17–25. https://doi.org/x.1007/s11019-007-9102-2.

-

Bingold TM, Lefering R, Zacharowski K, Waydhas C, Scheller B. Elf-Jahre-Kerndatensatz in der Intensivmedizin. Zunahmen von Fallschwere und Versorgungsaufwand. [Eleven years of cadre data set in intensive care medicine. Severity of affliction and workload are increasing]. Anaesthesist. 2014;63:942–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00101-014-2389-five.

-

Seidlein A-H, Hannich A, Nowak A, Gründling M, Salloch S. Ethical aspects of time in intensive care decision making. J Med Ethics. 2020. https://doi.org/ten.1136/medethics-2019-105752.

-

Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34:30–42.

-

Reiter-Theil South, Schürmann J. The 'big v' in 100 clinical ideals consultation cases: evaluating three years of ethics support in the Basel University Hospitals. Bioeth Forum. 2016;9:60–70.

-

Yoon NYS, Ong YT, Yap HW, Tay KT, Lim EG, Cheong CWS, et al. Evaluating assessment tools of the quality of clinical ideals consultations: a systematic scoping review from 1992 to 2019. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21:51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00492-4.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized past Projekt Deal. This study was not supported by any external funding.

Author data

Affiliations

Contributions

AN conceptualised the report, analysed and interpreted data, wrote the first draft and revised the manuscript. JS conceptualised the study, interpreted information and revised the manuscript. SN conceptualised the study, interpreted data and contributed to the manuscript. NH analysed and interpreted data and contributed to the manuscript. KPL interpreted information and contributed to the manuscript. Hr interpreted data and contributed to the manuscript. JD interpreted data and contributed to the manuscript. DS interpreted data and contributed to the manuscript. MN conceptualised the study, analysed and interpreted data, and contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and canonical the last manuscript.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Ethics blessing and consent to participate

The study was presented to the Ethics Commission of the Medical Faculty of the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg and received an exemption based on the utilise of anonymized data (Processing-Number: 2019-178). All methods were carried out in accord with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent is not applicable hither due to the methodology (retrospective evaluation of anonymized consultation protocols).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AN is the provider of the clinical ethics consultation at the university hospital presented in the study. JS is the provider and supervisor of the clinical ethics consultation at the university hospital presented in the study. SN declares that he has no known competing interests. NH declares that he has no known competing interests. KPL is a member of the CECC team at the said university infirmary and regularly renders legal communication in CECC. 60 minutes declares that he has no known competing interests. JD is a fellow in clinical cardiology at the university hospital presented in the study and co-author of recommendations for ethical determination-making in clinical cardiology and intensive care medicine (i.eastward. implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy, supportive cardiac care, organ donation). DS declares that he has no known competing interests. MN has initiated this CECC with JS and AN and was a member of the CECC team at the academy hospital presented in the report.

Boosted data

Publisher's Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This commodity is licensed nether a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilize, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other tertiary political party fabric in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If cloth is not included in the article's Creative Eatables licence and your intended apply is non permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the information fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the information.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Nowak, A., Schildmann, J., Nadolny, S. et al. Clinical ethics case consultation in a academy department of cardiology and intensive care: a descriptive evaluation of consultation protocols. BMC Med Ethics 22, 99 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00668-6

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12910-021-00668-6

Keywords

- Cardiology

- Clinical ideals

- Ethics consultation

- Evaluation research

- Intensive care - document analysis

winspearwhost1955.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12910-021-00668-6